From product to service: a transition

The shift towards a service economy is redefining the way societies produce, consume, and innovate. Although this is not a new phenomenon, its recent consolidation as the dominant driver of economic value reveals a profound transition: from the production of tangible goods to the generation of experiences, knowledge, and human capabilities.

Over the last few decades, virtually all countries have seen a progressive shift towards the service sector in their productive structure. Following the industrial era of the 20th century, services have become the dominant component of GDP and employment in advanced economies, and are gaining weight in emerging economies. For example, globally, the share of the service sector in GDP increased from ~53% in 1970 to ~67% in 2021, outpacing the relative growth of industry and agriculture. At the same time, global trade in services nearly doubled from 1990 to 2022, rising from 7.6% to 13.4% of GDP, thanks to technological advances and lower logistics costs. This phenomenon confirms the transition predicted by economists: from agrarian to industrial societies, and from industrial to post-industrial societies based on services.

But what is the service economy?

”The service economy (third sector) refers to a model in which most economic value comes from service activities (commerce, transportation, finance, education, health, leisure, administration, etc.), rather than the production of tangible goods.

This megatrend is not only a consequence of the classic tertiarization of economic development, but is also being driven by a combination of cultural, technological, and environmental factors. The result is an economy increasingly focused on providing comprehensive solutions and the “servitization” of products, where user experience and intangible added value take center stage.

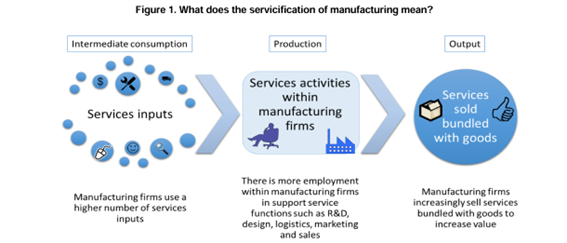

In conceptual terms, the “service economy” not only implies that more services are being produced, but also a transformation in the way value is generated. Many goods are being “servitized” (complemented or replaced by services) and the line between product and service is blurring. As a forward-looking report by the Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies points out, there is now a product-service continuum: companies no longer sell only pure products or services, but integrated solutions that combine both (a phenomenon known as servitization). A visible result of this is that the added value of services permeates the entire economy: even in the export of manufactured goods, 37% of the value comes from services (design, logistics, marketing, R&D, financing, etc.) according to OECD data.

The global economy is becoming increasingly tertiary and intangible, with an unprecedented emphasis on activities based on knowledge, information, experiences, and human capabilities.

Drivers of the megatrend: the PESTEL framework

The rise of the service economy is driven by multiple structural factors of a social, technological, economic, environmental, political, and ecological nature (PESTEL framework). The main drivers in each dimension are summarized below:

Social and cultural

Urbanization and demographic changes have increased demand for urban services, while the growth of the global middle class and per capita income is driving greater spending on education, health, leisure, tourism, and other consumer services. Culturally, younger generations place greater value on experiences (travel, entertainment, gastronomy) than on owning goods. This shift in preferences is also reflected in the sharing economy: there is a tendency to share or rent rather than own (housing, vehicles, tools), provided that the associated service is convenient. One example is the rise of car-sharing and content-streaming platforms, models that were unthinkable decades ago. In addition, in many developed countries, the aging population is driving demand for care and health services, while modern lifestyles are generating demand for personal services (childcare, wellness, fitness, etc.).

Twenty-first-century society—more connected, urban, and with new priorities—is structurally pushing toward an economy focused on providing specialized and personalized services.

Technological

Mass digitization is perhaps the most relevant factor for the service economy. Information and communication technologies (ICT) have radically reduced barriers of distance and scale, making it possible to provide services remotely and globally. On the one hand, they have enabled new digital services, from e-commerce to telemedicine. On the other hand, they have turned traditional services into 24/7 online offerings. Likewise, automation and AI improve productivity (e.g., chatbots handling routine queries, algorithms optimizing logistics routes), while creating entirely new categories (big data analysis, digital transformation consulting, etc.). In general, technology has facilitated the scalability of services: platforms such as Uber, Airbnb, and Amazon Web Services show how a digital model can serve millions of users globally, something that was impossible 20 years ago.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution continues to drive the “servicification” of the economy by converting physical functionalities into on-demand digital services.

Economical

There are powerful economic drivers that encourage the expansion of services. One is the structural change in development itself: as economies grow, agricultural and industrial productivity increases and employment shifts toward services (Fisher-Clark laws). The result is a natural increase in the weight of the tertiary sector as countries prosper. Another driver is globalization and trade liberalization: although trade in goods has slowed in recent years, trade in services is remarkably dynamic, and with digitalization, many services easily cross borders. Liberalization policies—such as the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) and numerous bilateral treaties—have been dismantling restrictions, opening up previously closed markets. For example, many countries have privatized public services or allowed foreign investment in banking and insurance. However, it should be noted that significant regulatory barriers remain, such as professional and data protection standards, indicating room for further growth if trade costs are reduced.

From a business perspective, another economic factor is specialization and outsourcing: companies have focused on their core activities and subcontract ancillary services (cleaning, logistics, IT, marketing), fueling the growth of specialized suppliers. The search for recurring revenue has also led many product companies to adopt associated service models (maintenance contracts, leasing, subscriptions) to stabilize revenue streams. Finally, advanced economies increasingly rely on intangible assets—human capital, R&D, patents, brands—whose returns are realized through high-value services (design, engineering, software, financial consulting, etc.).

A structural change in development has been detected, creating a virtuous circle: higher income and economic complexity lead to a greater role for services as a source of growth, employment, and innovation.

Environmental

Although it may seem counterintuitive, environmental and sustainability pressures also act as drivers of the service economy. On the one hand, the urgency of mitigating climate change and resource scarcity is promoting circular economy models, in which consumers pay to use a service rather than purchase a good, as in the case of car sharing. This approach encourages suppliers to design more durable, repairable, and efficient goods. On the other hand, many services are inherently less carbon-intensive than heavy manufacturing, or can contribute to reducing the carbon footprint in supply chains. All in all, the trend toward a more immaterial economy is seen by many experts as complementary to the sustainable agenda: it promotes “dematerialization” and greater resource sharing.

The ecological transition stimulates new services and business models aligned with sustainability, while reinforcing the idea of “using rather than owning” that underlies the service economy.

Political and institutional

Finally, political decisions and institutional frameworks have played a facilitating role. In many advanced economies, economic liberalization since the 1980s and 1990s has involved privatizing or deregulating service industries such as telecommunications, airlines, and finance, which has boosted these sectors through competition. Likewise, governments and international organizations have promoted reforms aimed at creating a “service society,” encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship in tertiary activities. Education policies focused on human capital, investment in R&D and digitization, and regulatory frameworks that guarantee competition (e.g., antitrust laws on digital platforms and user protection) are key elements for the sustainable growth of services. Political stability and the rule of law are also preconditions: services flourish best in strong institutional environments where contracts are respected, intellectual property is protected, and public-private partnerships in health, education, etc. are enabled.

Economic policy decisions over the last few decades have steered economies toward knowledge-based and intangible activities.

A new ecosystem of services: Signs of change and emerging trends

Numerous recent signs point to a transition toward a service-centered economy and foreshadow upcoming transformations. Among the most relevant emerging trends are:

Digital platforms and the on-demand economy

The last decade has seen the proliferation of online service platforms that instantly connect supply and demand, transforming entire sectors. Activities that were once occasional goods or transactions are now offered as continuous services via apps. This model of digital intermediation, known as the gig economy, has grown exponentially: globally, the platform economy is estimated to have generated some $3.8 trillion in revenue in 2022. Platforms such as Uber, Airbnb, and Deliveroo have improved efficiency and convenience for users, although they raise debates about labor regulation and competition.

Everything-as-a-service (XaaS) and the end of ownership

In line with the above, there is a cultural and market shift towards the Everything as a Service model. Increasingly, companies are offering physical products alongside associated services or replacing one-off sales with subscriptions and rentals. For example, industrial machinery manufacturers sell capacity or usage time through pay-per-hour models, software companies have migrated to cloud-based SaaS models instead of perpetual licenses, and even video games are consumed via streaming services.

Nothing belongs to me. I don’t have a car. I don’t own my house. I don’t own any appliances or clothes. – Ida Auken, Danish parliamentarian, in 2016, on the city of 2030.

The preference for flexibility and convenience is driving new generations to rent goods (cars, tools, even phones) and hire comprehensive services, blurring the lines between product and service.

Servitization of industry and hybrid solutions

Manufacturing companies are driving this change by adding layers of service around their products to provide more value and build customer loyalty. Today, every product comes with a built-in service, and many services replace the need for the product itself. A clear example is Rolls-Royce with its aircraft engines: it no longer sells the engine, but rather guaranteed flight hours (Power by the Hour), taking care of all maintenance—in other words, it sells a service outcome linked to its product. Similarly, services associated with smart products are becoming increasingly common, appliance companies are exploring offering their appliances on lease with repair services included, and car manufacturers are incorporating connectivity, insurance, or maintenance services into the sales package. This integration creates hybrid but complete solutions, rather than isolated goods, increasing the contribution of the intangible component to the final value.

Expansion of technology-enabled services (AI, big data)

Financial services have evolved toward fintech (mobile payments, algorithmic financial advice, crypto services), diversifying offerings beyond traditional banking. In healthcare, AI-assisted diagnostic services and remote patient monitoring via wearables are emerging. Education is experiencing a boom in online learning services that complement or replace face-to-face teaching. Even in sectors such as agriculture, agrotech services (satellite crop monitoring, meteorological and soil data subscriptions) are emerging and being integrated into the agricultural value chain. These technological innovations are not only creating new markets for specialized services, but are also increasing productivity in the tertiary sector. According to the World Bank, much more R&D spending is currently being done in services than in industry, and areas such as professional, scientific, and technical services are growing in importance in middle-income countries. These trends are transforming the nature of many service jobs, requiring new skilled profiles to develop and manage these technologies.

Remote work and globalization of talent

The COVID-19 pandemic, together with digital collaboration tools, has normalized teleworking and the provision of professional services remotely. In Spain, around 15% of workers work remotely on a regular or sporadic basis (compared to less than 5% before 2020). In northern European countries and the US, these figures are even higher. This has led to a “delocalization” of service work, rapidly expanding the global talent market. Currently, ~68% of all online freelancers worldwide reside in low- and middle-income countries, taking advantage of opportunities to export digital services. This trend is narrowing the traditional gap in service exports, offering emerging economies niches in the global service chain (e.g., the Philippines leads in BPO call centers, India in IT, Eastern Europe in software development). The current ecosystem is increasingly globalized and interconnected, where geographic location matters less than internet connection and skills. Remote work transcends sectors and drives competition for talent globally, posing challenges for training the local workforce in each country. The key is to avoid falling behind in digital skills and management of new technologies.

New policies and frameworks underpinning change

Finally, we are seeing signs in the regulatory sphere that are consolidating the service economy. For example, in early 2024, the WTO reached an agreement to facilitate internal procedures in trade in services (licenses, domestic regulation), with the potential to reduce trade costs by USD 150 billion annually. Likewise, many cities and governments are investing in digital infrastructure (5G, data centers, online public services) to enable more digital services. The European Union, for its part, is promoting regulations such as the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act to regulate the environment of large platforms and protect users, recognizing the centrality of these services in the economy. There are also massive training initiatives (such as the WEF’s Reskilling Revolution) to retrain workers for future service jobs. In developed countries, after decades of deindustrialization, post-COVID recovery strategies emphasize stimulating high value-added service sectors (e.g., the EU with its Digital Agenda and Next Generation funds for digital and green transformation, which largely finance services). All these institutional actions reinforce the signal that the global economy is preparing for a service-dominated era, laying the necessary regulatory and human capital foundations.

Challenges and tensions in the service era

Although the shift toward a service economy is clear and widely established, this transition faces significant structural challenges and generates socioeconomic tensions that require attention.

Job insecurity and job quality

Certain segments of the service sector, especially in the gig economy and platform jobs, are often based on independent work without the social protections of traditional employment. Problems of precariousness also persist in traditional service sectors, such as low wages in hospitality and retail, high temporary employment in seasonal tourism, and long subcontracting chains in ancillary services, such as cleaning and security, which dilute labor responsibilities.

Regulatory and public policy gaps

Faced with a rapidly evolving service sector, many of the current rules (tax, competition, consumer protection) are being put to the test. For example, how should digital services provided from another jurisdiction be taxed correctly? How can fair competition be ensured when network effects tend to create oligopolies on global platforms? In this context, the EU has responded with pioneering regulations such as the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act to limit abuses by large platforms. However, standardizing quality in international professional services, arbitrating disputes in cross-border services, and coordinating the regulation of highly complex services (such as those related to data and AI) are pending tasks in global governance. The speed of innovation in services requires an agile response from public policies, balancing protection and flexibility.

Digital gap

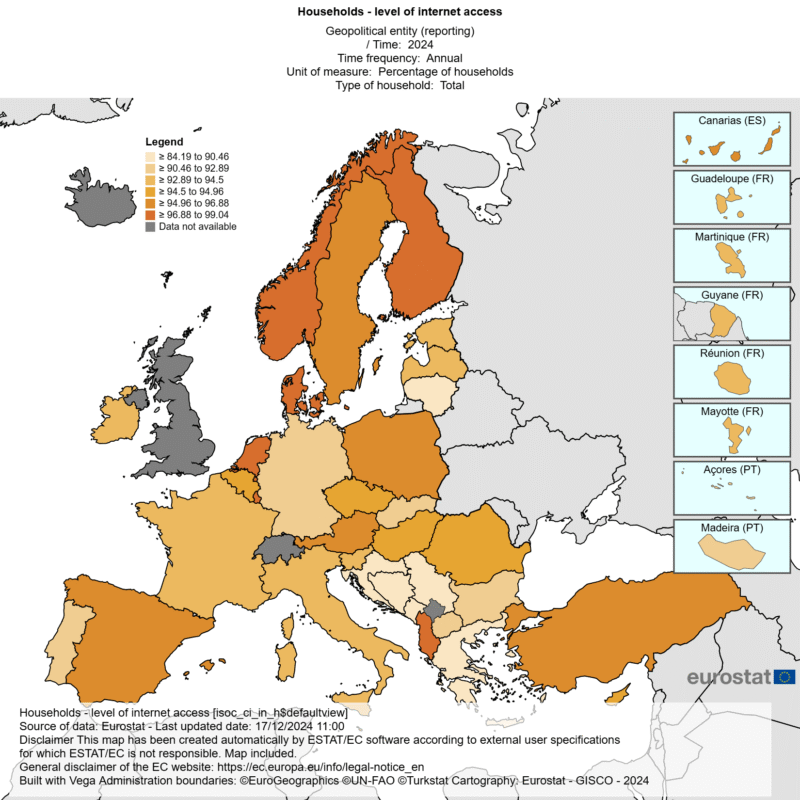

As more everyday activities, administrative procedures, and job opportunities move to online services, there is a risk of excluding those who lack access or sufficient digital skills. In the European Union, around 6% of the population (aged 16–74) has still never used the Internet, a figure that rises to double digits among older people or in specific rural regions. This gap is more pronounced globally, where billions of people in developing countries lack quality connectivity.

At the same time, the lack of digital skills, even in advanced societies, can marginalize vulnerable groups such as older adults, low-density rural areas, and people with lower levels of education. If government services, banking, education, and commerce become primarily digital, those who are offline will face additional barriers to fully exercising their rights and taking advantage of economic opportunities.

Environmental level

Although the transition to services promises benefits in terms of sustainability and reduced material impact, it also entails new ecological risks stemming from the increased energy demand associated with the digital economy. Data-intensive sectors such as cloud storage and processing centers are experiencing exponential growth in their carbon footprint, requiring innovative solutions to ensure that the service economy does not contradict global environmental goals.

An increasingly helpful future

Although the rise of the service economy is evident, its full consolidation will depend largely on our collective ability to adapt. Businesses, governments, and citizens must be prepared to navigate a complex environment in which technological innovation must be balanced with social equity, user protection, environmental sustainability, and effective international collaboration. More than a destination, the service economy presents itself as a constantly evolving path, requiring lifelong learning and proactive policies to ensure its long-term economic and social sustainability.

This megatrend is not merely a natural consequence of economic development, but a paradigmatic transformation of what it means to create value in the 21st century. Service becomes the new language of the economy to address an increasingly connected and sustainable world. Preparing for this future involves not only adapting to new forms of production and consumption, but also ensuring that the value generated is distributed equitably and resiliently.

References

- Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies (2023). Global Megatrends: Shaping the Future of Societies, Economies, and Values. SCENARIO Reports No 07. Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies. https://atelierdesfuturs.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/CIFS_Scenario_Report_Global_Megatrends.pdf

-

Eurostat (s. f.). Digital society statistics at regional level. Statistics Explained. Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Digital_society_statistics_at_regional_level

-

Foro Económico Mundial (2017). Ocho predicciones para el mundo en 2030. World Economic Forum. https://es.weforum.org/stories/2017/02/ocho-predicciones-para-el-mundo-en-2030/

-

Gill, Indermit (2021). “¿A su servicio? Las economías en desarrollo apuestan por el sector de servicios para crecer.” Banco Mundial (Blog). https://blogs.worldbank.org/es/voices/su-servicio-las-economias-en-desarrollo-apuestan-por-el-sector-de-servicios-para-crecer/

-

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2024). Encuesta sobre Equipamiento y Uso de Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación (TIC) en los Hogares. Nota de prensa. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/TICH2024.htm

-

Miroudot, S. y Cadestin, C. (2017). Services in Global Value Chains: From Inputs to Value-Creating Activities. OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 197. OECD Publishing, París. https://doi.org/10.1787/465f0d8b-en

-

OCDE (2024). Revitalising Services Trade for Global Growth: Evidence from Ten Years of Monitoring Services Trade Policies through the OECD STRI. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/3cc371ac-en

-

Upwork (2024). Gig Economy Statistics and Market Trends for 2025. Upwork Resources. https://www.upwork.com/resources/gig-economy-statistics